1820–1898

1820

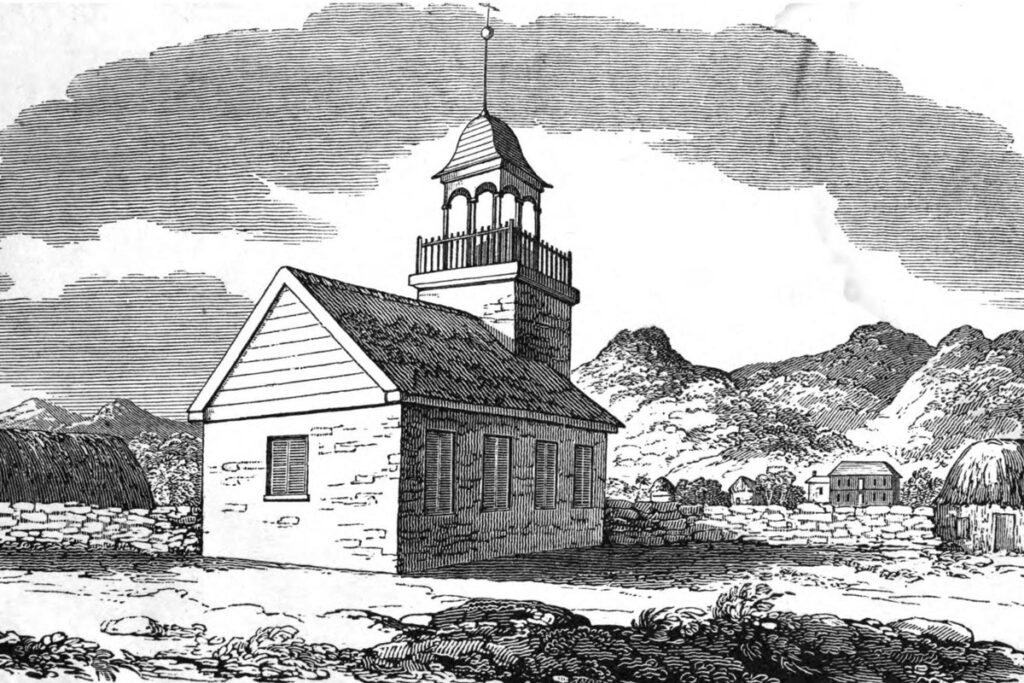

(April 4th) SS Thaddeus arrives to Kailua-Kona with 1st wave of American Missionaries

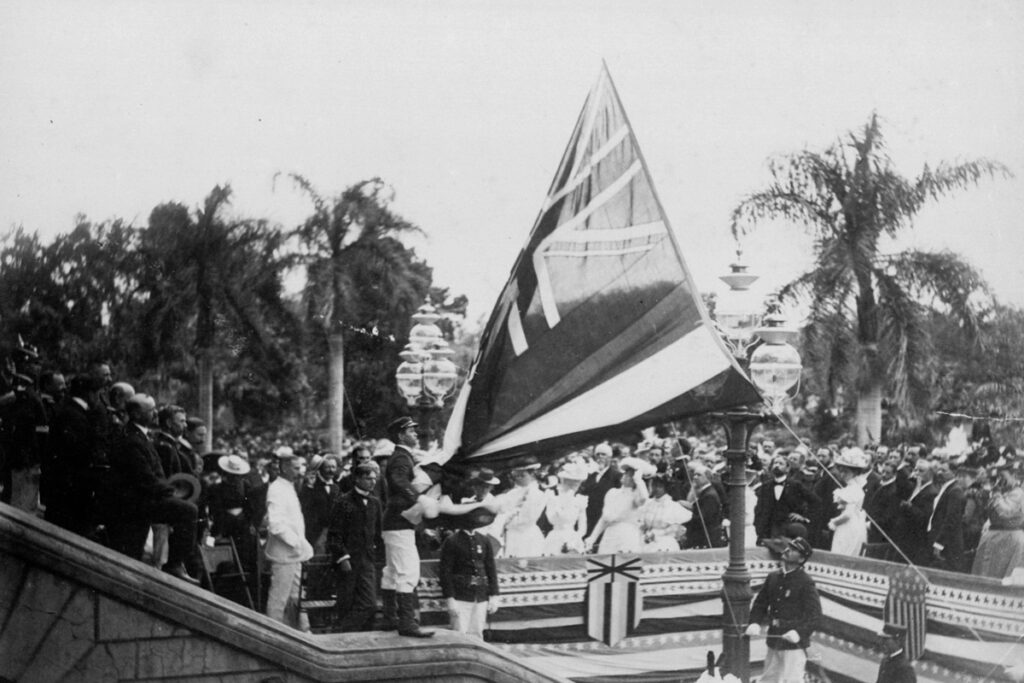

1898

U.S. Annexation

1900–1959

1907

McKinley HS (renamed from Honolulu HS)

1920

Hawaiian Homes Commission Act Passed (sponsored by Delegate Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole)

1941

Japan’s Attack on Pearl Harbor

1947

Gov. Ingram Stainbeck: declares “war on Communism” in Hawaiʻi

1948

Teachers John and Aiko Reneicke fired for Communist sympathies

1951-1953

Smith Act Trial of Hawaiʻi Seven (Communism Trial)

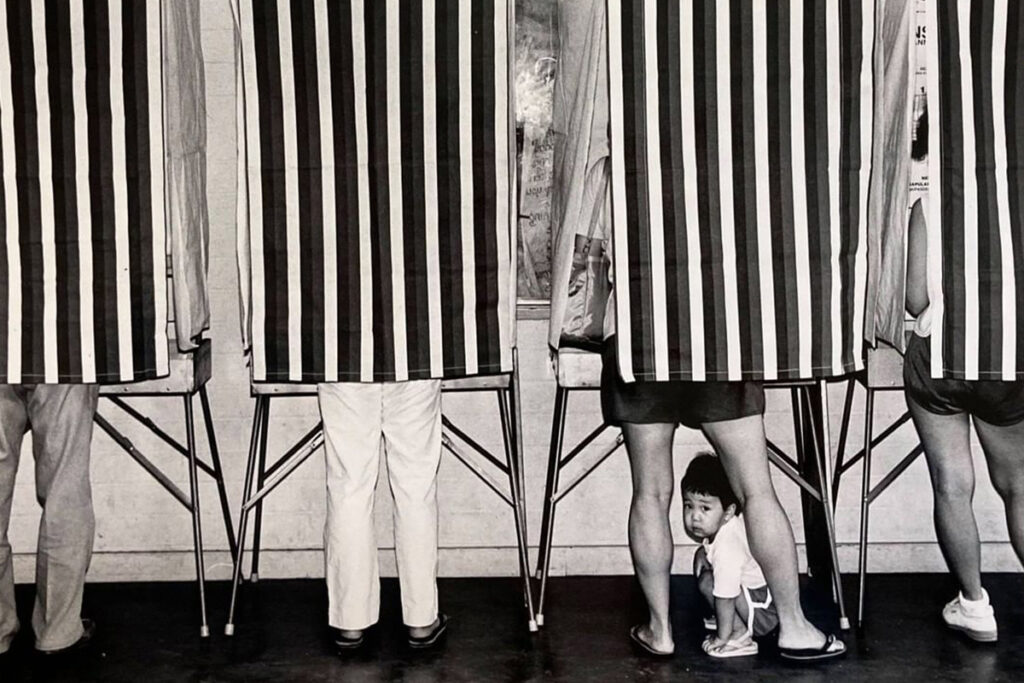

1954

Territorial Election: Democratic Takeover of Legislature

1970s onward

1990s

Protests against live-fire training in Makua Valley, Oʻahu

2010s

Resistance over further development of Mauna Kea on Hawaiʻi Island